On March 19, 2018 The New York Times published an article entitled “Extensive Data Shows Punishing Reach of Racism for Black Boys.” Drawing on longitudinal data on millions of American children, the research cited revealed that even when Black boys and white boys grew up in similar socioeconomic circumstances, the Black boys almost always went on to become men who earned less, often much less, than their white counterparts. Indeed, whereas rich white boys typically became rich men, wealthy Black boys were more likely to become poor than to remain wealthy.

These findings provided one point of departure for a conversation convened by Othering & Belonging Editor-in-chief Andrew Grant-Thomas on the following day. The participants were three African American scholar-activists deeply invested in naming, scrutinizing, and countering the othering of Black people and members of other marginalized communities—Erin Kerrison, School of Social Welfare, University of California, Berkeley; Wizdom Powell, Health Disparities Institute, University of Connecticut; and Abigail Sewell, Sociology, Emory University. An edited transcript of their conversation follows.

What does the term “othering” mean to each of you?

Wizdom: I think to be othered is to be denied the fullness of one’s humanity. It’s about reminding people, either by the barriers we put up in social spaces or the barriers to opportunities to advance our well-being, about saying through words or actions, that “you’re not one of us.” And I try to think about what it must be like for Black men and boys, for boys and men of color, to move through political and social spaces highly visible in some ways while invisibilized in others.

Abigail: I think there is also a suggestion, in addition to the alienation Wizdom is talking about, that one is intrinsically different from the “self” who does the othering, the self who is raised up as the ideal, the thing the “other” should be. So there’s a process of subordination happening when someone, or a group of people, is othered.

Erin: I love both of those definitions. I want to add that othering renders the subject as object. When you are rendered as object instead of subject, then anything can be done to you and it’s okay. We, the mainstream, the people who are not othered, the self to which other people need to aspire, can do whatever we want to you and you have no recourse. And I think that’s a really important part of being relegated to the object as opposed to the subject.

Wizdom: I love that because it makes me think about the challenge that we have, from a social science research perspective, when we consider white males as the group against which everybody else is compared. And every decision we make is about the relative distance between the others and this group. That has consequences just from the perspective of measuring population health. So othering has social and psychological consequences for the individual, but it also has impacts even on the data and the science and the stories we tell about communities that are vulnerable.

Abigail: You hit the nail on the head. When we talk about health disparities, people always want to know, “What is the ideal health outcome for a group?” But if white folks don’t always have the best health outcomes, why do we use them as the ideal self? As Wizdom says, that has clear implications for how we set up our studies—and what kind of research the National Institutes of Health supports, for example.

Understanding how inequality is created doesn’t necessarily mean focusing on group differences in health outcomes. Going back twenty years, we would study discrimination. And to understand discrimination we say, “Okay, we’ll put everything that can reasonably account for outcome disparities in the model and everything that’s left over we can attribute to discrimination.” But that actually doesn’t tell us anything except that we don’t have a good way of measuring what’s going on.

So I think the othering framework is actually really useful because it leads us to ask who the object is, who the subject is, and why some people are being objectified. To what purpose? Instead of that being in the background story, object and subject become the center of our analysis.

You’ve started to talk about the consequences of othering for the individual, for groups, and even for the science of inequality and the kind of research the National Institutes of Health supports. Let’s dig deeper into the matter of consequences. What specific consequences of othering most concerns you in your work?

Erin: I think a lot about the lack of attention paid to the health-related fallout of criminal justice policy and criminal justice interventions. So, yes, dying at the hands of a criminal justice agent is a bad health outcome, for sure. But what about the less dramatic health outcomes we typically don’t recognize as such—issues like anxiety, insomnia, fear of moving around in your neighborhood, e.g., Freddie Gray running after making eye contact with a police officer? We’re not counting those phenomena as important when we think about the fallout of policy and what it’s meant to achieve with respect to public safety.

That’s something I’m really hung up on with colleagues and the policymakers whose ears I have, but I’m not sure they’re willing to hear it because it requires understanding othered folks as subjects instead of objects. Poor health outcomes persist because we don’t even name them as health outcomes or we don’t name them as problems or challenges that need addressing. And that silence is in and of itself very, very violent.

Wizdom: Yes! I also think about the impact of being othered on the willingness or capacity of men and boys of color to be emotionally vulnerable, to disclose what’s really happening to them. To call a thing a thing, which is really important if you’re going to be made visible, to move from object to subject. Because objects don’t speak, right? They’re spoken to.

Erin: That’s very right.

Wizdom: I think that there are real consequences for the interior lives of boys and men of color that are related to their interactions with systems that other them, mute them, render them invisible. I’m concerned about how we sanction men and boys, particularly boys and men of color, around the disclosure of emotions in ways that leaves it almost impossible for them to seek social support. You can’t reap the benefits of the village if you believe being vulnerable is going to expose you to more threat.

I’m talking about both the immediate and lagged effects of that kind of process. We saw that with Kalief Browder. Here’s someone who emerged from incarceration as a symbol of social justice reform and crumbled under the weight of undiagnosed trauma. [Browder killed himself at age twenty-two.] He was met with, “Oh, you’re so resilient!” as opposed to, “What’s really happened to you and how can we help you get to the place in your life you want to be?” And that concerns me profoundly, not just as a psychologist, but as a woman, connected to men and boys in our community, who realizes that when they don’t live to experience life at its fullest potential we all suffer. Our fates are linked—as a Black woman, a sister, an aunt, as someone who’s profoundly connected to a community of men I love and care about.

What you’ve already all said underlines how hard, probably impossible, it is to disentangle causes and effects, the mechanisms of othering from the consequences of othering. But I do want to focus on mechanisms for a moment. What fuels othering as a social process in the spaces and among the groups you’re working with?

Abigail: If we want to have that conversation about mechanisms, then we have to start thinking about time. We have to start thinking about cohorts. We have to start thinking about how people disadvantaged within a space by economics or by racial or immigration status are unable to protect the next generation from the types of inequality they themselves were exposed to.

I think that’s one of the most remarkable things about the recent study talked about in The New York Times. It showed that even the most well-to-do Black people can’t protect their Black sons from poverty. People pass down wealth through intergenerational transfers and through the ability of beneficiaries to use wealth to create more wealth. But when we have poor schools, when we have a mass incarceration system that actually rewards stock owners when people are criminalized, then even Black people with money are spending that money to keep the next generation out of the criminal justice system instead of having them start their own businesses. So we can’t only think about what happened in the 1960s versus 1970s. We have to think of this from a life course perspective. For me that’s very fundamental.

When I think about mechanisms, I also can’t help but talk about policy. In fact, I think that’s the only reason I do the work I do—because I want it to be used to create policies that hold police accountable for their actions and their inactions, that support communities to intervene on their own behalf, and to establish an understanding at the federal level that having such huge disparities is evidence of a problem in the system itself.

Wizdom: What you said hits home on so many levels. What I think we’re bearing witness to, and have over generations, is a critical empathy gap for boys and men of color, in particular, and people of color, in general. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been in a room talking with passion about issues that are facing boys and men of color and I can see people checking their email or looking away or maybe planning their grocery list. And that’s concerning to me.

And yet I try all the time to make the case that this is about you! Because we’re in a significant demographic transition. We’re a browning nation and if we’re going to compete in the global marketplace, this is the labor force we have to be ready to deploy, the one we have to prepare for economic and social innovation. And so, the fact that people look away at this moment in time is striking. This is really about all of us. If we don’t get that now, we never will.

Erin, I’d like you to take up Wizdom’s point about the failure of empathy, about so many people checking out of the concerns she raises about the objectification of men and boys of color. And I also want to ask: are the dynamics of the othering of Black people different in kind or simply different in degree from the othering of other people of color?

I’m thinking about several conceptualizations of racial hierarchy in the United States. A common one sees white people at the top, Black and/or Native peoples at the bottom, and other groups arranged in between. Another sees the crucial division as between whites and “people of color,” and a third talks about Black people and non-Black people. And there are still others. With respect to othering, are Black people the canary in the coal mine, simply the group most vulnerable to the structural inequities that affect everybody, or are they subject to a different kind of othering altogether?

Erin: Okay. The question of empathy and of kind versus degree is helpful. Wizdom just talked about how often she’s been the only one in various spaces lifting up the uncomfortable truth about boys and men of color. But the first problem is that she’s too often the only one in those spaces who looks like us othered folks. So, that’s a huge part of it. We’re dealing with a crisis of segregation and exclusion where the movers and shakers who would shine a light on these very real problems that merit attention and remedies aren’t part of the conversation.

And that’s a huge, huge part of cultivating a culture of empathy. It’s not enough to say, “You should really care.” I think people are just straight-up not exposed. That’s a huge issue that we see in all groups, the movers and the shakers, and the policymakers and the legislators, but all the way down to lay citizens who go to voting booths and simply do not see the people for whom we’re advocating. They don’t see them, so of course they don’t see their pains. And those who ignore, deny them, I still say we can do better about winning them over.

Wizdom: I so appreciate your positivity about the potential for people to be transformed. As a positive psychologist, I can really appreciate that.

There’re probably more than two sides to othering. One is to say, “I don’t see you. You’re invisible. You’re not really relevant to me. There’s enough distance between you and me, social or otherwise, that you don’t even exist.” That’s one way to other. The other, more vicious, dangerous form of othering says, “I don’t see you” and “I don’t want you. I’m going to extinguish you.” That is what I’m seeing in my work with boys and men of color. It’s not only that they’re invisible. It’s that, “Even having you at the bottom of the social ladder is not enough distance. I want you below the ground.”

Abigail: My comments are pretty aligned with yours, Wizdom. Maybe, four or five years ago, I did believe that Black folks in particular were canaries in the coal mine. The economic recession really hit Black folks, Black families at a much earlier date, maybe three or four years before it hit the rest of United States. And it wasn’t just that nobody cared, it’s that people actually profited from it.

I want you all to wrap your minds around this for a minute. People on Wall Street made a lot of money off the recession. Not everybody lost. People just think that everybody lost, but some people knew it was coming. They knew that systematic failures within the mortgage market would topple the economy. They were able to get the government to bail them out after they made the damaging loans in the first place.

Yup. Failure in one respect. And we know that systems do exactly what they’re designed to do. The system worked!

Abigail: It’s not failure! It’s the system working as it should. Our American system is white nationalist at its core. It was designed to be a white nationalist system, so when it starts to look like they’re trying to kill us, when it looks like they don’t care, like they’re trying to make us sick—it was designed to be that way. “Our” system was built on settler colonialism. The right question is not how do we try to make the system work, but how do we tear it down?

It’s not to say that some individual minorities and poor people can’t win in this system. But if you’re working for the success of entire generations of those people, you have to create a system actually designed for their success.

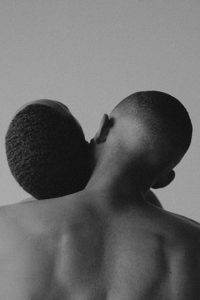

- Shikeith, What the World Sees Seeing Him

- Shikeith, Nobody Knows My Name, 2017

- Shikeith, Dreams in Black and White

- Shikeith, Germinate

Shikeith, Various Pieces

Good. Let’s talk about that. Imagine that here we are, sitting together in the year 2043—twenty-five years from now—and we’ve made significant progress along the dimensions of race, class, gender, and othering that we’ve been talking about. Give us a glimpse of what that might look like and then describe one or two crucial points in the intervening twenty-five years that have paved the way to this very new conversation we can now have.

Erin: I’m happy to jump in and I hope we can capture Abigail’s frowning because it was so perfect.

So what seed do we want to plant and have someone else come along and till, so that we might have better outcomes in twenty-five years? I’m thinking about the development of technology and the ways in which that’s incorporated in policy. I’m not optimistic. I’m not optimistic, especially thinking about surveillance and the emergence of big data. The idea of body-worn cameras on police as an accountability measure, for instance. We’ve never not had effigies and mementos of state violence against Black folks. There are families that still have heirlooms and artifacts of skin from lynched victims; I’m very serious about that. That these shrines exist and people are proud of them. We’ve never not known that these things were happening.

Twenty-five years from now, I don’t know that it’ll be better without a massive system overhaul—and I don’t mean anarchy. That’s about having imagination about what is possible for us, and who we include as citizens and what we want for our youth. I’m happy to go on record saying I’m cynical and I’d love to be convinced otherwise as an activist who’s committed to this work, so that I don’t feel completely defeated. I’m still in it with you and always will be, but it is something I think about given that we’re operating in a context that is working exactly the way it’s supposed to.

Erin, we can come back to you in a bit, if you like, because I do want you to take up the challenge, which is what the seed of transformation would look like. What might just one seed look like? And relatedly, is anything happening now that gives you some hope, that holds some promise? So let’s come back to that, but, Wizdom or Abigail, want to offer any thoughts you have?

Wizdom: This question forces me to think about how little progress we’ve made thus far, and to have to face the really stark reality that in twenty-five years things may not be much different. But I do believe one excellent sign of having arrived at a better place would be when the so-called other can live life without fearing that other people will think of them as less than or expect deference whenever they enter a room.

I think the only catalyst for that is to build a nation of disruptors. We can’t catalyze change if we teach a generation of youth, Brown and Black youths in particular, to be quiet and silent about social injustice. At a time when facts and evidence are doubted or treated as false, more truth, alone, isn’t going to bring us to a freer place.

I also believe there has to be a more fervent movement towards love within the communities that are objectified. I talk about altruistic love as the great equalizer for people who are marginalized because when you love someone who looks like you, you behave in ways that are prosocial. You do things that uplift community and you are able to really catalyze social justice. No social justice movement or change can happen without love. I am all about upstream change, structural change; we need that. But if we create that change and are still broken in it, it’s not going to work out well for us in the next twenty-five years.

Abigail: I love the idea of a nation of disruptors. We definitely need that. The question is how will they disrupt things. Now, some people would assume that they’re going to break buildings, set fire to everything, overturn cop cars. But I think there are much more effective ways to disrupt.

Looking ahead to the 2018 midterm elections, we had 100 million eligible voters who did not vote in the last election. 100 million! That’s about the number who did vote. How disruptive would those missing 100 million votes have been to the current state of affairs? I respect anybody’s right to bow out and recognize that our political system is set up to discourage people from voting. That also tells me where the next possible solution is. When you remove the barriers to voting and participating in our political system, to helping hold different institutional actors accountable for the things that they do, you’re going to see a different system.

I am part of that generation of people who use the internet to create things that never existed, to take down things that should not have existed, to build communities that rely on more than physical connection. I think digital platforms have a lot of disruptive power. Unfortunately, a lot of people are trying to corporatize and privatize the internet right now and we need those 100 million people to show up and show out.

Erin: You restore my hope; thank you! On my lowest days, when I’m really feeling empty about where we’re headed and whether we can dig ourselves out of them, I remember and place a lot of value on bearing witness. On sitting with the discomfort and ugliness. On telling the truth unapologetically, without mincing words, being brave about telling a story that folks don’t want to hear.

Zora Neale Hurston said, “If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.” With respect to planting seeds of progress, I think that’s a huge thing that needs to continue. Then no one can say we didn’t tell them.

Abigail, I loved what you said about the digital platforms through which people can show up and show out, because it’s true. In addition to the harmful effects of gerrymandering and long waits to vote and short polling hours, lack of political participation is also about people not being able to see the benefits of participation. Leveraging digital platforms to include the voices and perspectives of marginalized people is actually a huge move forward. I think that is one very healthy and productive way of building a critical mass of folks who could overhaul these systems, of building up spaces so that folks, once again, are subject instead of object.

If the folks who read this could have seen your expressions when I first asked you to envision the substantial progress we might make over the next twenty-five years, some would have said, “Oh wow, that’s really cynical.” And yet you all lead the most uncynical lives, right? You are activists and advocates, living the life of the mind and also doing the practical, on-the-ground social change work.

In closing, could each of you say a word about how it is that in spite of your deep concern, even skepticism, that we can make real progress even in twenty-five years, you choose to spend your time pushing for that change.

Wizdom: I’ve always questioned why other people are treated unjustly or unfairly, and that fire in my belly is rekindled daily as I watch us move through the world. Having survived the Transatlantic Slave Trade and Jim Crow and lynching and a campaign of white terror, still we get up every day and love on each other, and celebrate, and create music and art and film, and inspire each other through a simple, “What’s up, sis?” That energy, our capacity not just to survive but to thrive, keeps me going.

In my opinion, there is nothing more patriotic than a Black person going to work every day, paying taxes. Seeing all the Black people who persist in a society that constantly tells them through word and deed that they don’t matter—that keeps me going. Remembering that it was the everyday acts of resistance that brought us to this place. It was because Harriet said, “I’m going to go back and get some more people,” even in though people probably looked at her like she was crazy.

Some days I think this is hard work. I can’t watch another Black man, Black woman being shot down in the street like a dog. But then I think, “what would Harriet do?” She didn’t give up and I can’t. I have the luxury of a warm house and a good salary and a husband I love. We don’t have to live on separate plantations and he doesn’t have to sneak out in the middle of the night so we can be together. I do believe in many ways that I’m called to this purpose. Every day it’s the thing that gets me out of bed.

Erin: This is an easy answer from me, Andrew, and thank you for inviting us to share why and how we keep getting up. As you said, Wizdom, people must have looked at Harriet Tubman like she was crazy. Coincidentally, she did have a traumatic brain injury. She had a traumatic brain injury and still saved all those souls. She literally had half a mind and still killed it. I just love that. But I think about her and I think, “How dare I not do this work?” Before I even existed, there was the vision of me, there was the promise of me for whom she was fighting. And so, I owe her at least that. It’s just that simple. And I hope that what she dreamt for me will be reproduced in what I dream for those who come after me.

The rest is just one foot in front of the other. It really is. I’m reminded of that by you guys. You guys are so beautiful and brilliant, and I think about all the privilege that we have and we know it would make no sense not to do these things. It’s really energizing too when you know you’re on the right side of history. I think about a righteous covenant that I have with my ancestors who risked everything, everything so that I could read, so that I could be on a panel like this. That’s crazy. I think about having a vicious imagination for what’s possible; how dare we not push forward for that?

Wizdom: I don’t want to break in because I know Abigail has to speak, but I just have to weigh in on this point you made about what to give back to people who fought for a reality that they would never live to see. What’s more loving than that? How do you even say to yourself you’re not going to do it? How do you get up and fight for a right to vote or to be free or to read when you yourself may never read a book?

Erin: You’re giving me chills. I have a hard enough time getting up going to the gym for a body that I know that I want in this lifetime, right? Those folks fought for me. It just becomes a no-brainer. But go ahead, Abigail.

Abigail: I love what you all are saying. It’s giving me a lot of energy right now. I’ll give several people credit in my answer. One is my sister who asked me what I wanted to do with my life—this is after I was accepted into graduate school but before I had started. And I said, “Oh, I want to do this, I want to do that,” a lot of stuff around policy and activism. She said, “Don’t wait until you’re finished. Do it now.”

I also had a close friend in college ask me, “Where will you be when the revolution happens?” The question has really haunted me over the years. I remember asking someone else that question and she said, “We won’t be the revolution; we’ll be the ones who usher in the revolutionaries.” And I’ve taken that charge to heart. Everybody I come into contact with, every student, every faculty colleague, I’m just out there trying to usher them into their revolutionary state.

And then the last thing is: I’ve never lived in a world that can give me everything I’ve ever wanted, but that’s what I want for the next generation. I hold on to the idea that the world that has yet to be shaped is a world that I would actually want to live in. I do the work I do because I’m not satisfied with the world as it is.

Wizdom: Over time I’ve become less concerned with what my role in the revolution will be and pretty clear that my role is probably going to be very, very small. I don’t see that as problematic. I think about the Keymaker in The Matrix, whose only role is to open the door. If I have to hold the door or open the door, I’m going to play that part and I think that’s how we have to see ourselves in this fight. Today I’m holding the door, tomorrow I’m opening the door. And whatever role I’m supposed to play on this battlefield I’ll play it because I understand that I’m so minuscule to the overall design and divine plan.

Erin: One second! Minuscule but necessary. Minuscule but critical. It wouldn’t function without you. But that is how the universe works.

Abigail: Exactly.

Some years ago I tried to put together an edited volume premised on a version of the question I posed earlier. I asked thirty to forty social justice workers what their corner of the universe would look like in twenty-five years if they were wildly successful in their work. Few people could answer that question in a vivid and compelling, affirmative way—because it’s hard. What would systems transformation look like? How do we make strategic moves toward a world we literally can’t imagine?

And then I remember the words of E.L. Doctorow, who said that “Writing a novel is like driving a car at night. You can see only as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.” He was talking about writing, but I think it applies equally well to the struggle we’re all engaged in.

Thank you.