The 2016 US presidential campaign was marked by extraordinarily explicit expressions of animus and resentment toward “difference,” whether along lines of race, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, nationality, religion, or ability. Many believe that Donald Trump won the presidency not in spite of but largely on the strength of his bigotry, his xenophobia, and his rhetorical assault on immigrants and Muslim Americans, in particular—and on the strength of his promise to back his words with corresponding policies.

And, of course, “Trumpism” is hardly the only way in which matters of identity shape the tenor of our times. Black Lives Matter. Blue Lives Matter. Native Lives Matter. All Lives Matter. Dreamers. Border walls. #HeretoStay. Deportation Forces. Muslim registry. Sanctuary cities and schools. Standing Rock. Many parents, teachers, and other caregivers have found themselves dismayed and unprepared to help the children they love navigate these turbulent waters.

O&B approached Allison Briscoe-Smith and Maureen Costello, two experts on children, child development, race, and social othering for their observations and insights.

Contributors

Allison Briscoe-Smith completed her internship and postdoctoral fellowship at the University of California, San Francisco, at San Francisco General Hospital, where she specialized in child-parent psychotherapy and working with traumatized populations. Throughout her training, her studies focused on child psychopathology and diversity issues. After her postdoctoral work, Dr. Briscoe-Smith was the program director of a mental health program serving children as they entered the Alameda County foster care system. She was a professor of child psychology at Palo Alto University for four years and served as the director of Children’s Hospital Oakland’s Center for the Vulnerable Child for three years. She is now an adjunct professor at the Wright Institute and a consultant to nonprofit organizations seeking to become trauma-informed and culturally accountable. Dr. Briscoe-Smith’s research has focused on trauma/post-traumatic stress disorder and how children understand race. She has worked broadly on these topics and has served many families and schools on matters salient to these issues.

Maureen Costello brings over thirty years of education and publishing experience to her roles as director of Teaching Tolerance and member of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s senior leadership team. Beginning with her years as a history and economics teacher at Staten Island’s Notre Dame Academy High School, Costello has committed her career to fostering the ideals of democracy and citizenship in young people. After leaving the classroom, she directed the Newsweek Education Program, which was dedicated to engaging high school and college students in issues of public concern. Immediately before joining Teaching Tolerance, she oversaw development of the 2010 Census in Schools program for Scholastic Inc., in partnership with the US Census Bureau. Costello is a graduate of the New School University and the New York University Graduate School of Arts & Science.

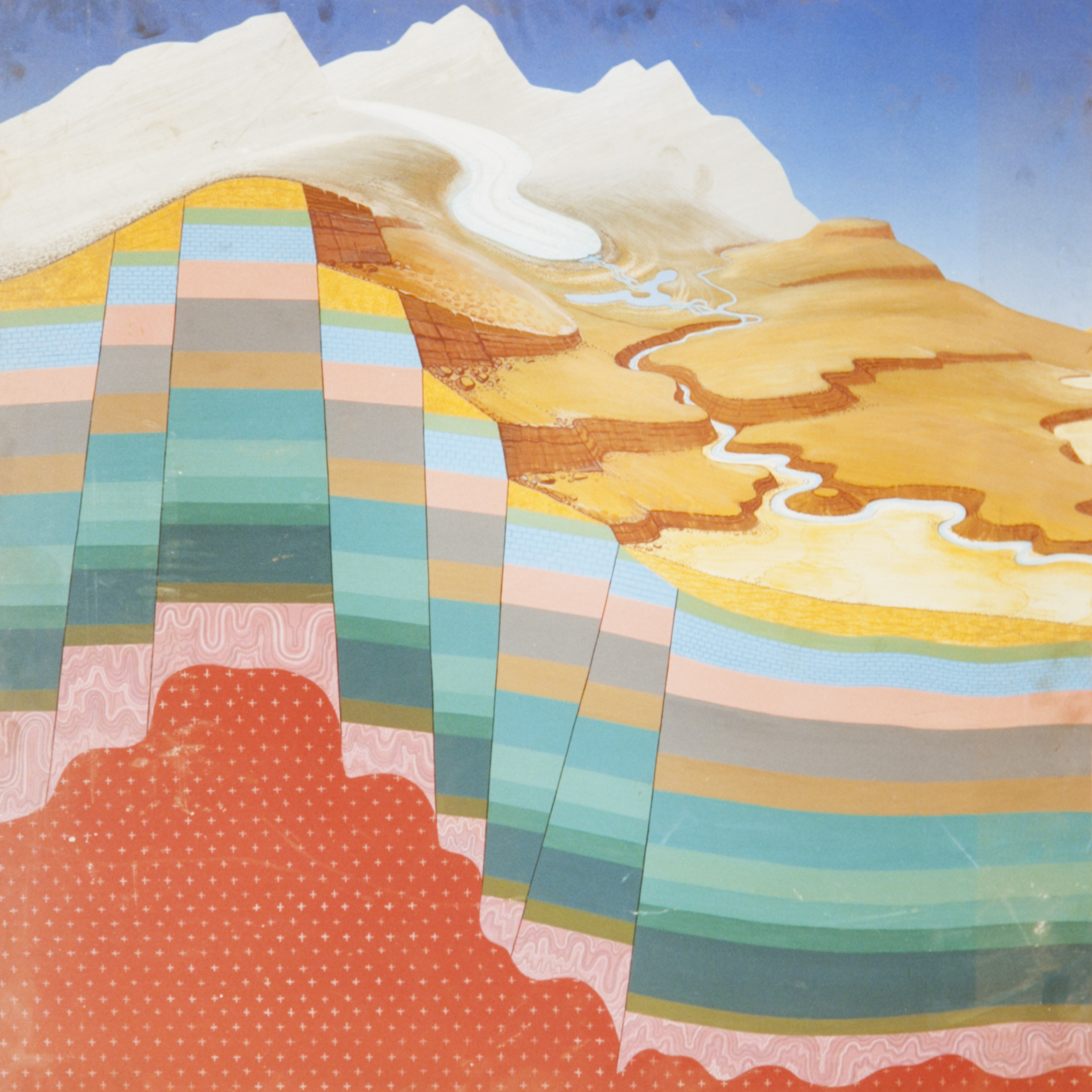

Yto Barrada | Untitled (painted educational boards found in Natural History Museum, never opened, Azilal, Morocco; fig. 1-6), 2013-2015

chromogenic print | 70 cm x 70 cm (27-9/16” x 27-9/16”) each of 6 prints

© Yto Barrada, courtesy Pace London; Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg, Beirut; and Galerie Polaris, Paris

Installation view of Yto Barrada: Faux Guide, presented at Pace London, Jun 26, 2015 – Aug 08, 2015

Photography by Damian Griffiths

Just in the two weeks after Election Day 2016, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) catalogued some nine hundred hate incidents, most of them directed at immigrants, blacks, LGBTQ people, Muslims, Jews, and women. And, of course, the vast majority of bias incidents aren’t reported publicly. What is your sense right now about how kids are processing all this?

Maureen: At the same time we reported those hate incidents, SPLC also reported on the results of a survey we sent out to teachers a week after the election. Over a period of two weeks, we received more than ten thousand responses. Nine thousand teachers reported that school climate had been negatively affected by the election, and eight thousand of them thought it would linger through the year. They reported that the vulnerable kids you ask about—immigrants, LGBTQ, Muslims, women, and African Americans—are having a hard time. Sometimes that’s because they’re experiencing outright harassment from peers, but even in the absence of harassment, they are deeply worried, anxious, and sometimes angry. They’re dealing with two big issues: first, what the election seems to say about how valued, and valuable, they are to people in this country; and second, what kinds of policies are going to come down the pike.

That second set of worries is very real and hard for the adults around them to explain away. No one knows what is going to happen, in terms of immigration policy, or whether there will be a registry for Muslims, or whether women and African Americans will face fewer opportunities and LGBTQ rights will be rolled back. The issue of feeling less valued also is very real. I’ve heard from countless educators that their vulnerable students feel dejected, heartbroken, unwanted, and hated. In some cases, they’re trying to hide who they are. Some are missing school, and they’re experiencing bullying and harassment. It’s very troubling.

Allison: My sense is that children have been increasingly faced with explicit messages directed against particular groups, whether it’s immigrants, brown people, or, increasingly, Jewish folks as well. Kids are trying to make sense of all of this. And I think it’s coming up in terms of the questions they have about other people, the fears they express, but also playing out in terms of bullying. The message kids receive about who’s powerful and who’s not plays out in their dynamics. The SPLC also reported a lot of anxiety among black and brown kids and kids from immigrant families, who’re also suffering high rates of bullying. So kids pick up on and use societal messages to understand themselves and their positions but also to relate to each other.

What core mechanisms—cognitive, social, emotional, linguistic, or otherwise—shape the development of a child’s sensibilities toward identity differences (i.e., “others”)?

Allison: I think it’s important to begin with the cognitive and understand that kids are not “little adults.” They have different brains, cognitive functioning, and emotional processing and are oriented differently than adults socially. It’s a key point: they are not little adults. Kids are really organized to make sense of the world according to difference; they are looking for difference. But it’s really we, adults, who socialize kids to fear difference. It’s really on us to teach them that difference and “other” aren’t inherently bad or scary, but rather something we can investigate, be curious about, and be in relationship with. So the core mechanism really is the development of the child’s brain.

And then there’s an important social dimension—Are they in a homogeneous or heterogeneous social environment? How much access do they have to their friends? What kind of implicit and explicit socialization messages are they getting from their parents, which also helps kids understand whether or not difference is bad? So, again, we must be explicit in helping kids understand that difference doesn’t mean bad; it just means different. And those are the two mechanisms I pay most attention to: the socialization part and the cognitive part.

Maureen: Many of these are psychological processes that have resulted from human evolution. We know that, even in infancy, children develop a preference for faces that look like their main caregiver. Before they enter school, their social lives are centered around family or a limited sphere of people selected by the family and may have little exposure to difference. Moreover, they grow up in a society that has entrenched beliefs and narratives about racial, ethnic, and other differences—beliefs so entrenched that they are invisible to a child. We know that social biases begin to form as early as ages three to five, and children begin to attribute negative or positive traits to others based on how they look or how they fit into categories.

What’s often missing is a proactive counter to the developing sensibilities. When they encounter difference, children are curious and want to understand it. Too often, the adults around them are afraid to talk about it and send out messages that the subject is off limits or somehow shameful. That is a huge missed opportunity because the best way to balance our natural tendency to sort and categorize and to isolate ourselves from others is to work at positive identity formation and socialization that includes others. Adults too often let society or their silence shape children’s ideas about difference rather than setting out to shape those ideas proactively.

In the midst of an extended period of elevated expressions of explicit bigotry in US political and social life, many caregivers want to know what they can do and say to nurture children inclined to embrace rather than “other” their peers along lines of race, gender, religion, culture, and gender expression? What general advice can you offer?

Maureen: Talk is powerful. Having an open disposition that invites questions about difference and being comfortable answering them is absolutely necessary. Having the willingness to bring the topic up, noting differences, and building useful and positive narratives in children’s minds is even better. These narratives acknowledge difference and talk about stereotyping and prejudice. Children shouldn’t be brought up to believe that differences don’t exist or that they don’t mean anything or that it’s impolite to talk about them. They need age-appropriate facts about difference, relationships and exposure to people who are different, and information about how difference can bring on unfair treatment.

Allison: The overarching question I’m often asked is: What can I possibly say to help children understand what’s going on and how not to “other”? I think parents need to be paying attention not only to what they’re saying but also to what they’re doing. How are parents carrying themselves? How do they interact across difference? Are they anxious and nervous when they encounter difference or are they open and flexible? Do children meet with difference in their homes and elsewhere? Parents have a big opportunity to model for kids how to interact with others.

Think about your environment: Is your environment a space that provides access to difference? Or is it predominantly homogenous? Do you have books that feature different types of people in different roles? I just saw an interesting video clip where a mother and a daughter went through a section of a bookstore and looked at how many of the books had girl characters, how many of those girl characters actually spoke, how many of them were featured centrally, and how traditional their roles were—how many were princesses being rescued, for example. There can be real thoughtfulness about representation in the home in terms of books, the kinds of pictures we have on our walls, the kinds of stories we tell. Parents also have the opportunity to identify and root kids in our own family values and how the family wants to engage others.

Yto Barrada | Untitled (painted educational boards found in Natural History Museum, never opened, Azilal, Morocco; fig. 4 of 6), 2013-2015

chromogenic print | 70 cm x 70 cm (27-9/16” x 27-9/16”)

© Yto Barrada, courtesy Pace London; Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg, Beirut; and Galerie Polaris, Paris

What can adults do to promote resiliency in those children most likely to be targeted for bullying or other forms of othering?

Allison: The big piece I like to focus on with promoting resiliency in the kids most likely to be targeted—Howard Stevenson talks about this in the context of storytelling—is giving kids access to stories of resistance and resilience. They need to hear the stories about how their parents and grandparents dealt with and overcame discrimination. Books are very important, especially with respect to issues of representation, but we can’t relegate such stories to books alone, to the realm of fantasy. We must connect children to proximal stories of resistance and resilience, and to history: we have been through this before. We’ve been through iterations of this, and we’re still surviving and thriving. Connecting with stories of how we’ve done that and are doing that is super important for kids.

Maureen: Sharing their own stories of vulnerability is a good start. Too often, we adults want to provide a set of instructions to kids. But it’s very powerful to let them know that we haven’t always had the answers, and maybe still don’t. A parent can let a child know that she’s bothered by something someone said and then think out loud about how she’s going to deal with it. Most importantly, help kids talk about what they’re feeling, mentally review their alternatives, and work out plans together. Take the child seriously and listen to her or him without brushing aside the bullying or talking about what the perpetrator intended or resorting to platitudes like “sticks and stones.” Resiliency comes from knowing someone believes you, sees you as a full human being, and helps you to find your strengths. And, finally, help the child form a rich web of social relationships.

What kinds of antiothering or probelonging policies or practices would you personally like to see implemented and enforced in more PK-12 schools?

Maureen: I’d like to see school leaders set high expectations for all staff, from teachers to bus drivers, about the need to treat each child and each family with respect and dignity and back these up with training. Inclusivity and positive identity should drive lots of choices, from curriculum to books in the school library, to what’s on the bulletin boards. Kids should be given lots of opportunities to learn and work with different peers and not be segregated into silos of special ed. or gifted programs or fast readers or jocks. There should be at least one student-led organization that promotes diversity, such as a Gay-Straight Alliance club or a Stand Tall against Racism group. Empathy, perspective taking, and hearing multiple stories and points of view should be practiced regularly. Ideally, I’d love it if schools were more like resort hotels, where everyone on staff is focused on making the experience a good one for every kid.

Allison: There is huge opportunity in the context of schools. I think the schools that are utilizing approaches like restorative justice circles, opportunities for people to really engage and develop tools for mediating conflict and speak to their own experiences, are great. I think schools that have a big focus on social and emotional learning, empathy, connecting, and antibullying—schools that have curriculums that attend to values and the character of hearts and minds—can do excellent work. And there are schools that teach about history and are thoughtful about representation and help our kids engage critically with history and with current events while being grounded in emotional literacy and an ability to negotiate conflict. And I’m actually really hopeful that we’re on that pathway of doing this.